WHOSE MUSIC IS IT ANYWAY? (Part 3/5)

What the internet has done to the music industry.

March 16, 2016

Dominic McGonigal - C8 Associates

That ‘giant billboard in the sky and virtual jukebox’, read here, has led to an explosion of consumption, but most of it is free. This has had a profound effect on the music industry.

Before the internet, the vast majority of record company income came from sales of records. This delivered substantial revenues, with good margins. In fact, worldwide revenue for recorded music increased year-on-year, peaking at $33bn in around 2003.

Now, the revenue is around $15bn – less than half what it was twelve years ago. And yet, consumption has gone up. What has happened?

The first reason for this is obviously piracy. Shawn Fanning, a brilliant and creative developer, created peer-to-peer software when he was 18 years old. Apparently, he spent 60 hours writing the code for peer-to-peer file-sharing without a break. He named it ‘Napster’ and released it in June 1999. Within weeks, about 80 million people downloaded Napster on to their PCs to share files.

Napster was actually closed down in 2001, just two years later. But by that time there was a growing number of Napster clones e.g. Kazaa, Limewire and later BitTorrent. Essentially, the peer-to-peer technology became more and more networked and less and less reliant on a central server. The availability of free music was too much of a temptation for many. Just as significant though is the new model ‘post first, license later’. Platforms such as YouTube allow its users to upload any video with the platform using the ‘safe harbour’ provision to absolve itself of responsibility for the content, legal or illegal. Instead, they have a takedown procedure where any rightholder can request that an infringing file be taken down. Rather than this being the exception, it has become the rule. YouTube receives over 15m requests to take down an infringing file, every week. And when faced with a choice of something or nothing, many rightholders will accept a low royalty, rather than go to the expense of all the takedown notices. This explains the relatively low revenue from the enormous consumption on these platforms.

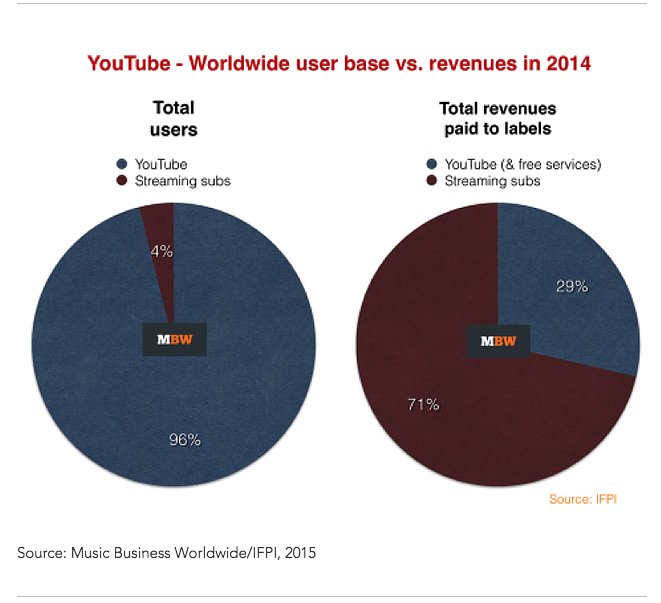

Let’s take a look at some numbers:

YouTube is far and away the largest streaming platform online. Its 1bn monthly users generate just $600m for the music industry. By comparison, the streaming services, with just 41m users, generate $1.6bn. The difference is highlighted by looking at the gross revenue per user. A streaming customer typically pays $120 a year for a premium subscription. That same consumer using YouTube is worth about 60c, per year.

But the ‘post first, license later’ model has a more significant impact. It effectively means everything is available free, no matter how many takedown notices are sent. Why would a consumer pay for music when everything is available free, even streaming continuously similar tracks for you. Back in the old days, the baseline was a budget album (around £2). Now, the baseline is £0. In order to compete, the freemium services such as Spotify have to offer the entire catalogue free and find other ways to upsell to a subscription.

That has led to a decline in sales revenue (physical and online combined), while the biggest form of music consumption, streaming, delivers just 24% of revenues. The world’s largest streaming service and largest platform for music consumption, YouTube, produces about 2% of total recorded music income. Live music revenues have increased in recent years, but not enough to plug the gap.

Record companies and publishers can still make a margin in the business, but when topline revenues halve, there is little room for investment in anything but a bankable hit. That explains why catalogue sales overtook sales of current releases in the USA for the first time last year.

It is easier to plan for a modest return licensing a back catalogue than to risk investment in a new release.

The blog mini series Whose Music Is It, Anyway? is based on a guest lecture given byDominic McGonigal at Trinity College, Dublin in February 2016.

Dominic McGonigal is Chairman of C8 Associates, a consultancy dedicated to taking creative businesses to the next level. He also chairs two creative startups, CICI and JazzUK. Read more at www.c8associates.com